Sean M. Conrey

Fate and the Emergence of a Poem

There are many ways of theorizing how we may know when a poem is done, and if we are to theorize at all, rather than rely on our genius to do so, then we must admit that any theory would be predicated on how we define what a poem is to us. Different definitions lead to different possibilities. But one common feature to all definitions is that the poem is a made thing, which means that it has a beginning and end that are discrete enough that readers will recognize them and grant the poem a unique place in their language and among the other things we live with every day. But this place should be earned, and different kinds of poetry earn their place as new creations in different ways.[1]

We rely to some degree on our own genius to tell us when a poem has earned such a place, but that doesn’t mean that this genius is a complete mystery. Try asking the 23-year-old Bob Dylan how he knew when “Blowing in the Wind” was done and you’d likely get a blank stare, a smirk and something like “because it was done.” But this obstinacy or inability to describe how a poem is done isn’t necessarily inarticulate. (And I often wonder, for example, how often poets actually hide behind this ethical ruse in order to protect the work and themselves from simplistic biographical explanations.) Our natural ability to intuit when a poem is done is often remarkable, and it’s fascinating how we can sometimes seem to know without being able to articulate how we know. The problem is, of course, that sometimes we can’t seem to intuit the poem’s completion, and it’s in these moments that we could stand a bit of artful consideration. For artful consideration, the situation must be theorized, and, again, if we want to theorize, we have to define our terms. In this way, the argument I am making becomes in ways a parallel to the point that I’m trying to make. Arguments and poems are both shaped, we could say, by fate.

In definition we can already begin to feel fate taking hold. As words come to have edges and boundaries, they become mortal and bound to particular paths of action. Through further and further refining, an argument has its own destiny, not unlike the task of finishing a poem— the task of refining, like defining, both have their root in the same Latin word, finis: end. Definitions have ends and edges and lead us toward an end. We give arguments and poems shape as we write them by evaluating how people use a word, how the dictionary defines a word, how scholars have thought of a word, and we begin to make a room for the word by giving it walls made of other words. Once the walls (and windows and gates and trap doors) are in place, we have a natural understanding that the word is not everything to everyone. It has shape, and can’t do everything, but perhaps just a few things well. It is destined, as itself and as we define it, to particular ends.[2] Once we have written something, some avenues and vistas open, and others close. Once we admit words on a page, especially if we define those words, a particular fate may not yet be sealed, but have no doubt, some fate awaits us. We can’t just say anything at that point.

How this refining emerges toward an end is what I want to talk about, particularly how we can see the poem has having a destination, which is a “destined” or fated, end. The act of arguing about the fate of a poem is, as I said before, parallel in ways to the point I’m making. We can see, as the argument unfolds, how its fate takes shape. This is the case with arguments and is very similar, and often more easily seen, to how poems take shape.

~*~

We’ll start, then by defining a poem as a meaningful and metrical text that, in having a textual beginning, is destined toward some textual end. Obviously, this is not the only definition of a poem we could make. But we’ll use this one and see where it takes us. First we need to clarify what is meant by “a meaningful and metrical text.”

Meaningful

By meaningful I mean “having reasonable, ethical and emotional consequences in the life of the reader-audience.” This definition comes loosely from Aristotle’s Rhetoric, where he systematically considers how when we talk to each other, we can artfully select our words by considering 1) the reasonable aspect of language (on which he focused much of his other philosophical work), 2) the ethical aspect of language, or how we trust people of various characters, and, by extension in a modern context, how we trust written documents of (and by) various characters, and 3) the emotional aspect of language, which grounds and drives much of human communication because we all feel something all the time. Meaning, then, for this argument and in Aristotle, is never solely found in the words themselves in some logical tyranny (how could it be, anyway?), but also in the richer rhetorical situation of language, namely trust and emotion.

At the risk of sounding pedantic, meaning is accordingly understood as being consequential in the life of not only the writer, but also the reader-audience; it is inextricably tied to the life of anyone who attends to it, and cannot be even theoretically removed from that life without severely detrimental side-effects. Words act on, with, and through audiences and readers and they gather and transmit their meanings always and already in this context. Aristotle gives us a rich way of articulating how meaning goes beyond the mere wordplay of the dictionary. Meaning is a living, tactile and visceral experience. To say otherwise would cut off an avenue for exploring the topic at hand.[3]

These three aspects of meaning— reasonable, ethical and emotional— play into and act on each other, one collapsing and changing the next in a reciprocal and often mysterious way. At various times in intellectual history, one has been foregrounded over others, leading to different paths of thought (different destinations, we might say), but I would try to recover them as equal, a kind of trinity of how words mean, where none is superior or more relevant in our everyday experience. Just as each is equal to the others at the level of experience, each is grounded in our experience in its own way. In the crafting of a poem, however, we may need to put one more to the fore than others for the sake of choice and art (as when we consciously work to fix a logical discrepancy in a poem, for example), but we would not want to mistake our emphasis at a particular time for how they live equally together before we considered what to do with them. With this in mind, and considering that we are trying to define what we mean by the “meaningful” aspect of a poem, the three aspects of meaning are more elaborately discussed as follows. Language is:

Reasonable

The reasonable aspect of meaning, to utterly simplify the difficult work of logicians for the sake of time and space, concerns itself with the interplay of words to words (definition) and words to observable and sayable phenomena (facts). It is through definition that we clarify words for the sake of argument, and it is through fact that we ground our words in experience and observation.

A well-reasoned argument, as I alluded previously, has a destiny that is in ways much more knowable, as we reach its conclusion, than a poem. We can outline it, say it in shorter or longer order, graph it, make it explicit. Reason’s many uses come from this explicit way of communicating, and while I’ll not focus on its uses here, suffice to say that Aristotle, in his logical works (the “Organon,” as they are called) set the tone for how we reasoned up until the early 20th century, and pretty often even after. Poems, like anything made of words, have this reasonable aspect of meaning. Language doesn’t work without it. But the tropes and devices of poetry so common to poets and readers of poetry don’t develop their meaning exclusively through reason, and in tropes and figures we must turn to some other aspect of language than the reasonable to theorize how such meaning takes place. Definition and fact obviously bind us to particular trajectories and paths of thinking and acting when we write, but they don’t make up the whole of meaning, and as that is the case, they don’t exclusively direct the course and destiny of a piece of writing, whether straight argumentation or something more poetic, as it emerges.

Ethical

The part of meaning gotten through the ethical aspect of language is most-clearly seen in how we trust words to do their work in the situation where they are uttered. When I ask a waiter for a beer, I don’t receive a walnut. This is, in part, because words are logical (the word “beer” was, in fact, long ago tied to a particular kind of thing, as was “walnut”). We trust the words to not only be logical, we also trust the waiter, the brewer, the friend who’s buying the round and typically the whole apparatus of the situation where the ordering takes place to do its work through the language of our request. It is a ramifying map of trust made of people, things, the expectations of physics etc. that places the word into the situation, implicating an action (the arrival of the beer) to occur. Again, like reason, language doesn’t work without its ground, which in this case is this web of trust and belief. But perhaps more needs to be said to place this in light of the history of ethics in general, and of the argument about fate and poetry in particular.

Typically ethics, as a philosophical study, involves people learning to think about right action, learning to do the right thing at the right time and be good people. The Greek word ethos, where we get the word ethics, is wrapped up in this, but is also concerned in a broader sense with the web of trust described previously. We trust people, when we think about it, because we believe they are good (or at least good for us) in some way. They are trustworthy. In this way it’s clear that ethics is a way of grounding our language in other people, in a “community” (which is rooted in the same place as “communication,” after all). It is through ethics that we most-obviously see how language works with others, but it is not exclusively about our trust in other people.

The ethical aspect of meaning is also about the ways in which people involve themselves in the lives of places and things. It is, in this way, the glue that holds us together (similar in ways to the ways in which facts are tied to each other in our experience) and it cannot be said to always be explicitly understood. Nor is it merely a thing of words. I almost never, for example again, even consider the intricacies of the act of ordering a beer when I do so. I typically don’t have to. I trust it will work out as expected. And when it doesn’t, I consider other options. Having, say, been told that the brand I ordered is out, I put another order in, hoping it will do its work without much of a thought. I probably have been made abreast of the situation (“the distributor is having a hard time getting that one” or that “the waiter broke the last bottle on the way from the back”) and that has destined me for another future. I have trust in the whole active communion of people, places, and things that I am involved in at that time, and the meaning of my words at that moment is comprised, we might say, of the connections that find momentary order when I say them there, then.

This, of course, presents a particular difficulty for writers. From the earliest critics of the written word (Plato being one of the most significant early commentators), it has been understood that there is something problematic about writing in that writing, being tied to a page and transported so easily across time and from place to place, makes its meaning where it arrives, not exclusively where it is written. This is very different from speaking in person, and accordingly it comes with a different ethics.[4] This causes Plato in his Phaedrus to debate that writing cannot participate wholly in the movement of the soul (as he says it), because it says the same words no matter what or where you ask it. What happens to ethics when the web of trust where the piece will arrive can’t necessarily be predicted by the writer? The answer cannot be answered easily in this short essay, but suffice to say that every writer, whether knowingly or unknowingly, participates in the discovery and recovery of this question. How can I weave my writing into the fabric of a moment not knowing where, when or with whom that moment will arise? I leave it to the reader to explore this, as inevitably they will, and would encourage them to consider Plato’s question and the dozens of thinkers after him who have tried to frame this question adequately.[5]

The intricacies of how this happens in a written poem will be discussed later (as a matter of, as Coleridge calls it “Poetic Faith). In a unique way, it is within this web of trust, both on and off the page, that we see the destiny of a poem emerge. But for now let’s put the question to the back of our mind and move on.

Emotional

The emotional aspect of language is perhaps the most difficult to talk about, and much has been recently written on this topic.[6] Where the ethical aspect of meaning is more about social connection, the emotional aspect of language is more private. I say “more social” and “more private,” because they are not wholly or exclusively one or the other. Ethics are a private affair, too, but more public. Emotions are more private, but there is also, obviously, something we share with each other emotionally. As with reason and ethics, language cannot work without emotion because people, the purveyors, conveyors and surveyors of language, are never without emotion. So just as ethics is not as simple as explicitly knowing what is good and what is not good (it is also tied to the deeper social bonds and connections that hold us to the world in which we live), the emotions, or pathe as they are called in Greek, ground us and connect us to the living fabric of the world around us in their own way. In this way, the pathe are more than emotions as we are used to talking about them. They are also the bodily ground of the emotions, that in which the emotions are felt. Our bodies, while so obviously participant in the physical world around us, are also limited in what they may explicitly and knowingly do.

Bear with this digression, if you will: Said another way, as long as we have a world, and within that world are things called “bodies,” we have limits.[7] We might even say that nouns prove it to be so. If we are going to have something called nouns, if we are going to have something instead of nothing, in other words, we are going to have limits and boundaries. In this fact we can understand, for instance, that I cannot lift an eighteen-wheeler over my head. Our bodies, as that in which, through which, and with which we feel, are bound perhaps in a similar way. If we are going to bother to give ourselves a name, and delimit the body as a significant part of who we “are,” then we might see how the body provides an initial terminus for action. I cannot do everything or nothing because I have a body. My noun-ness makes it so. Having named my body, and having named the senses, I work within the limits ascribed accordingly. The pathe are both the feelings that are tied into this limited body and the body in which they reside. Both reveal other ways we are attached to the world and both, in consort, help guide us through the limits, the horizons of meaning, of the world in which we act. They help guide us to various destinations.

Since writing is an action, and we feel deeply when we write (at least when things are going well), then we can see some of the ways that these feelings will limit, encourage and discourage particular paths of action. We will sense, perhaps without being able to reasonably describe why, that something is amiss when we write, and the same is true when we read. Words are bound into this deeply-felt apparatus of meaning, and, as with any kind of binding, we typically cannot escape its clutches as they guide us, so mysteriously, toward their ends.[8]

Think, for example, how we find ourselves sometimes at wit’s end (emotion having forced us to the end of reason’s plank) because we have followed our heart on some matter. We find ourselves in love and we desire to see this person as often as possible, or we find ourselves filled with hatred and driven to violence. There is a kind of fate that unravels in the midst of such feelings. In a similar way, emotions drive our hand when we write and also bind readers in particular, visceral, ways when we read. Just because we cannot rationalize how particular words or phrases on the page do this (and cannot, therefore, explain all their various possible fates) does not mean that they don’t guide us into particular avenues and paths of action. Obviously, they do. Every writer knows this in a deep and abiding way. But here I want to emphasize how the emotions contained in the words we use when we write are just as important (and perhaps even as theorizable, if we wanted to go further) as reason and ethics. As they are just as important in how they mean, they are just as important in how they delimit and open various ways for us to proceed when we write. Surely it’s clear to anyone who’s read more than one book that literature is very often a study in how people have, against all reason, fated themselves to a particular end. Surely it’s clear to anyone who writes that we, as writers, are as implicated in these same feelings as the characters we would create. When we are writing, we are no different. Those same feelings drive us to particular meaningful ends, just as they do in every other thing we do.

~*~

But all of that only covers the first primary word of the definition of a poem: meaning. I have dwelled on this word because I believe in ways it is perhaps the hardest to articulate and also, perhaps not coincidentally, the one that remains most often beyond our vision as we artfully consider the various pressures and energies that would compel us toward particular ends when we write. With any luck, this gives at least a rough model for how meaning might be said to play into the fate of a poem as it emerges. If so, then I suppose we are warranted in moving on.

Metrical

To go back, I have said that a poem is “a meaningful and metrical text that, in having a textual beginning, is destined toward some textual end,” but what is meant by “metrical?” Here I mean that the words of a poem are “measured, in time, in relation to each other and to the whole in a way that emphasizes and multiplies meaning.” In this definition it’s clear that in ways I am reifying the old assumption about form and meaning are intimately tied together.

Of the first part of the definition, for the sake of brevity, I’ll trust that the “measurement in time” is clear enough to anyone reading this. The standard practices of prosody and scansion are what I mean here.[9] “In relation to each other and to the whole,” though, may need a bit of clarification.

Scansion, as a study and practice, tends to focus on the relationships of words to each other in lines, with rhythm across lines playing a role in pattern and variation etc. When I say that meter deals with relations between words and each other and to the whole, I mean that the meter plays out at different scales, and that the placement of a particular poetic foot in a particular place affects not just the line itself, but the whole poem. This might go without saying, but it’s important to state this fact if we are to understand the next part of the definition, which states “in a way that emphasizes and multiplies meaning.”

Words placed in particular places in the poem lose or gain emphasis, depending on where they fall. First and last words in lines, first and last words in stanzas, rhymes with each other, especially the second or subsequent rhyming word, etc. all help a word or phrase gain emphasis. To emphasize meaning then means to recognize that the meaning of a particular part of the poem, and thus the poem as a whole, changes when one aspect is emphasized over another. This is something that we do naturally when we speak, and again the standards of prosody and scansion help us discover how the poem should be arranged when speaking it, but we shouldn’t forget that the page has its own agenda when it comes to emphasis. The tone deaf pages of a dictionary, for example, largely fail to understand emphasis, because words are made so equal on its pages, arbitrarily arranged as they are alphabetically, all in the same typeface with only bold and italic words standing out. But poets know that the space of the page (and the ways that that placement plays out when read aloud) change the emphasis, and thus the meaning of particular words and phrases, and thus the poem as a whole.

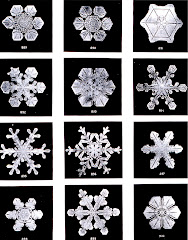

And the placement of words does more than just emphasize particular meanings in a poem, it also creates graphic and sonic resonances in the language that multiply meanings, creating, in the simplest forms, double entendres, puns and the like, but also connotations that exist exclusively in this particular configuration of words on a page. These connotations, as new and unexpected layers of meaning, are much of what great poetry does in terms of adding new and salient possibilities to language and are part of what makes every true poem unique. As these words are emphasized and multiplied because of their placement in meter and form, they come to act on each other: ramifying and opening new pathways in language, they build a unique meaning-structure. The words of a poem only ever mean what they mean in the context of that poem. As if by fate, when a poem is finished there is simply no other way to say it.

Text

But we also have to clarify what is meant by text, and to do this, I’ll start with something a bit more logical and move toward something more mythical. It is in this word that we perhaps get the clearest sense of what is meant by poems having a fate. Let’s start first with a more logical consideration of the term.

Text, Logically

The word text comes from the Latin texere, which means “to weave.” So, a text, like a textile, is a “weaving-together.” There is a lot of evidence in this regard because we already talk about texts in this way. We say that there are various “threads” of a conversation, for example. When we want to finish talking to someone, we “tie things up.” We call lies “fabrications,” insinuating that they are artificial patches on an otherwise (presumably) truthful quilt of language. But I don’t want to make a claim that a text is something exclusively made of words. In a broader sense, the world is a text, a weaving-together of the various people, places and things that make it up, a vast living fabric imbued with meaning.

What we make of that meaning is not exclusively a matter of words. The majority of things in the world, after all, go about their textual work without knowing, or even caring to know, the difference between a noun and a verb. The intimate connections between birds and worms, say, or between a stream and a mountainside. Even as language users, we can see how the non-verbal texture of the world reveals itself. We say that we feel “tied down” with family obligations, or “tied up” at work, for example. What we are tied to isn’t exclusively words, it is also the physical bounds of an office or home, the fact that we can only do so much in a day, that we must sleep at night, that the food we eat empowers us only so much. The weave of things in this way is all around us, confining (another “fin” word) and delimiting, but also freeing us by opening doors and pathways. The weave of the text is far more than words, and it is this weave that reveals and hides our fate as we live and, subsequently, when we write.

Poetry, concerned with weaving its threads primarily with words (and the affect those words have with a reader-audience), makes its texts largely of words, and adds layers of meaning, one over the other, so as to seem a worthy analog to the otherwise unwieldy, dark and brilliant bolts of living fabric that occasionally reveal themselves to us. In ways similar to how our obligations and physical limitations give our lives shape at any given time, the opening and closing paths of language that transpire when we write oblige and limit what that language can say and do. We can feel this viscerally when we write. Consider, for example, when we are writing and we find ourselves at a loss for words because the words already on the page are a kind of dead end. They leave us with little else to say but they insinuate that more must still be said. This is a common occurrence with writer’s block. Now consider, too, how erasing the offending paragraph or stanza, like untying a few rows of knitting, gives us a sense of relief because we have undone what got us in this position in the first place. Through revision we can feel the text open to us as new possibilities. Our fate is no longer sealed.

So, to come back to where we started, a poem is “a meaningful and metrical text that, in having a textual beginning, is destined toward some textual end.” We have covered what is meant by meaningful (“having logical, ethical and emotional consequences in the life of the reader-audience”), and what is meant by metrical (“measured, in time, in relation to each other and to the whole in a way that emphasizes and multiplies meaning”), and I have tried to cover logically what is meant by text by showing the root of the word; it is a weaving-together. But let’s turn to the mythic for a deeper understanding of text, as well. In myths around the world we see images over and over again where anything created is woven into the fabric of creation. It is this “weaving together” this “textuality,” if you will, that makes the discussion of fate, and by extension, the fate of the poem, possible.

Text, Mythically

In Germanic mythology (which shares many common threads with Greek and Roman mythology), the three weavers of Fate, the Norns as they are called, are Wyrd, who spins the thread of one’s life into being, Verðandi, (literally “that which is becoming”), who measures the thread of one’s life, and Skuld, who cuts the thread at life’s end. In this worldview, the lives of people, places and things are woven together by the various weavers of fate, and the choices we make, the oaths we take and break, the uncanny and unpredictable things that seemingly come from nowhere, shape our lives and weave a fate for each of us. Thus each life is poetic, in a way, with a beginning, middle, and end, and, should it be lived well (the logic would follow), one’s life could well be a great poem. It is no surprise, then, that the highest honor for the ancient Germanic peoples was to be remembered by a poet after your death.

The Anglos-Saxons, who we are indebted to not just for our language but much of our worldview, articulated their deep belief in fate with the phrase wyrd bið ful aræd: “fate goes as fate must,” or “fate is inexorable.” This idea, if not the phrase itself, appears in most of the more important extant Anglo-Saxon poetry. Consider, for example, that Beowulf makes oaths to his king and people and then to the Danes who he comes to save, and in doing so he limits the paths his life will take. The doom that befalls him at the end, as he dies battling the dragon that threatens the land and people he is pledged to, is not so much the fruition of tragic faults that we see in Greek literature (a fate focused on the negative), but the conclusion of his life’s poem, written by the choices he made for good and ill.[10] The choices he made, which are irrevocable, lead to a particular end. His oaths finally combine with the uncanny fabric of the world and settle upon him, and he dies, a doomed hero who accepts his death knowing that his story is worthy of remembrance. His life has had form and shape. Although that shape may well have remained uncanny and unknown to Beowulf himself, in the hands of a poet, it is clarified (and perhaps even simplified) so the reader can more readily feel it. So it goes.

The parallels between making a shapely life and making a poem are worth mentioning. If, as I defined, a poem is a meaningful and metrical text that, in having a textual beginning, is destined toward some textual end, then what begins in the text with the initial turn of phrase is measured (metered, we could say) and brought to a close (Wyrd, Verðandi, and Skuld each having their say). Because the words come about of a particular time and place, and with a particular poet who brings his or her own reasonable, ethical and emotional biases and skills (or lack therein), the fate of the words is set into motion from the poem’s beginning, lives through the process of the poem’s becoming, and is cut from its authorial umbilical by the hand of the poet. The one primary difference between the way a life could be said to be shaped (as with Beowulf), and the writing of a poem, is that as writers we may revoke words as we work toward a poem’s destiny, and thereby change its course. In our lives, we can’t do this. The best we can hope for is forgiveness, to be given again a chance to change what came before. In the Germanic worldview, from our very beginning, we begin to work toward some end, unknown and uncanny to us. Time passes relentlessly and fate is written during that time. But we can rework and refine a written poem, and perhaps there is a different kind of hope that comes with this kind of creative power.[11] Facing our own mistakes, we can forgive ourselves. This is a weird position to be in. Poets get their name, after all, from the Greek poiesis, to create, and perhaps this is why poets are often viewed as divine or prophetic; only a divine creator (or someone empowered to call on the divine) would have the power to revoke and change the conditions of the creation after the fact. As poets, our creations don’t suffer the same fate as others do.

Beginnings and Endings

Which brings us finally to beginnings and endings.

We have yet to really talk about beginnings and ends in any definitive detail. Beginnings and endings are the same thing, really, but in different directions. They are both terminal, meaning that they have limits; they are definitive in that they allow for finality; they are poetic in that they set apart a thing in the world. In these ways we can say that a beginning is just an end in reverse, and vice versa. But let’s start with beginnings.

There are two kinds of beginnings that I can think of that are worth considering in a poem when thinking about this notion of the poem having a fate: 1) the beginning in terms of “the initial admission of words onto the page,” the beginning of the writing process, and 2) the actual beginning of the poem for the reader, seen most obviously as the words in the upper left hand corner. The first kind of beginning typically comes first chronologically in the writing process, so I’ll start there.

Beginnings 1

It’s no coincidence that poets say that they work with the poem “from its conception,” as its beginning has a lot in common with other organic conceptions, where something is lit with the spark of life and emerges in light of that beginning. From its conception, then, we must admit that something new has entered the fray and therefore has a beginning, as such. But we’d be wise to remember that the words initially introduced may not actually be the first words of the poem. They are just the first words introduced to the page. From this initial moment, we add and subtract as needed and the thing ebbs and flows in its word count and tropes as we work toward assembling the parts together into some kind of comprehensive whole. But how do those initial words begin to push on an end? I’d claim that this process unfolds as some kind of three-way dialog (a trialog, I guess we could call it) between the poet, the page, and the reader-audience.

From the admission of the first words onto the page, a series of ramifying connections is made between the words of the poem with each other (both in meaning and meter)[12]. If we place even a few words on a page, from the moment those words forge a beginning they establish a meaningful and metrical connection with each other that, if written well, will bring the reader into the world of the poem and hold him or her there until the poem’s end. We do this all in light of the reasonable, ethical and emotional predilections we have as we write. The poem is a palimpsest of moods and thoughts in this way, as we work day after day on the poem we massage the words into place and the complexity of the emotions and thoughts we have while writing inform and determine how it will go. It is in light of these emotions and thoughts that we work toward making meaning and meter and thus it is in light of the same that the poem is fated to become what it will be.

Seeing the act of composition this way (where the connections between the meaningful and metrical aspects of words bind the poem together), insinuates that there is, if enough connections get made, a destination that the poet will arrive at eventually. We will intuit this perhaps more than know it sometimes. The connections that have been made shut out other possible directions for the poem to take like a game of word-chess that is finished when there are no more possible moves.

Beginnings 2

In the matter of the second kind of beginning, the actual first words of the poem, the consideration of the reader is even more important. Here before we talk about the words in the upper left of the page, we as writers also need to admit that the reader brings a particular mood to the poem before they even glance at the first words on the page, and this can’t really be completely accounted for by the poet. Thus the beginning of the poem takes place not exclusively on the upper left hand corner of the page, but as something read in a mood of the reader which exists before the poem is taken up. This is crucial for understanding the deeper connections between the poem and the reader: the reader’s mood is logically prior to the poem first taking place, and the poem begins to take shape in the midst of that mood. This is not to say that the meaning or the beginning of the poem is a wholly subjective experience, but that the poem’s fate is written in light of the fact that a reader will bring their mood and experience to the page. While the poem begins physically in the upper left corner of the page, it only emerges as a meaningful beginning in the hands of a reader. (Thus answering the question: if a poem blows through the woods and there’s no one there to read it, does it mean anything?)

With the onset of the poem, the reader is brought in and, assuming the meaningful and metrical connections are sound and make sense with each other and for the reader, then the reader will retain something akin to what Coleridge called “poetic faith.”[13] This poetic faith can be lost by breaching either the meaningful aspect (say, a severe unwarranted break from grammatical structure, or the inadvertent misuse of a word), or the metrical aspect (as when the meter established from the poem’s beginning fails to follow its natural course). Both of these aspects build an ongoing contract with the reader, and the further the reader gets into the poem, the greater the expectations are for the contract to continue.[14] This growth of expectation, we could say, is the reader feeling the uncanny fate of the poem unfold. They don’t know where the poem is going, but they are willingly along for the ride. If the poem can do these things to its conclusion, if the meaning and meter follow their destined course, then the poem can be said to be complete and whole. It has definition (although not in the logical sense), because it has been finally refined. If we pay attention to these things, I believe, we can begin to see how the fate of the poem develops and we can finally start talking about endings.

~*~

Similar to there being two kinds of beginnings, we can say that there are two kinds of ends (that correlate well with their opposite). We’ll detail these two ends in reverse order from our discussion of beginnings to complete the chiasmus of this section, so to speak.[15] There is the end of the poem for the reader, and the end of the poem for the poet, which is when the poem is done being written.

Endings 1

Just as the poem begins not exclusively in the top left of the page but also in the mood that the reader brings to the page, the end of the poem for the reader is not the last line, but the denouement that emerges from having read the last line of a good poem. The first kind of ending to consider is the relationship between the last word and the mood it weaves with the reader. The denouement, then, is that moment after the last word is read and a reader is held there as if by some force beyond themselves or the poem. After the last word, there is something more.

It is interesting in a discussion of how we weave the fate of a poem, then, because denouement means “to untie” in French. But to understand the implications of this, we’ll have to digress a bit, as it may seem logically confusing at first to say that the poem unties itself. The implication, if the metaphor is followed through, is that the threads come undone, and that might still be true. We’d want to careful, however, to make sure to understand that the threads don’t sit there idle, doing nothing. If the poem has succeeded, the threads have become untied from the page and become interwoven with the life of the reader. A new texture has been achieved and the fate of the reader is now tied into the fate of the poem. In its greatest success, a poem never truly leaves a reader, but will demand a lifelong tie to the poem, woven deeply into the text of the reader’s life. Perhaps this is what the Anglo-Saxons intuited when they talked of becoming immortalized in poetry; it’s a genealogical lineage that recognizes this relationship through time?[16]

Endings 2

the second kind of ending is closely tied to the first. If it were as simple as saying “the end is when you stop writing,” then there would be no criteria to speak of, nothing to say beyond “the poem ends when I say so.” Such theories do little to help us when we write, and truly demean the task at hand by making it seem arbitrary when it clearly is not (since so many readers agree when great poetry succeeds in finding its shape, it would seem to more than just arbitrarily-created coincidence). I have said that “in having a textual beginning, a poem is destined toward some textual end,” and it is this destiny that I want, finally, to talk about.

Just as the poem ends in denouement with the reader and not exclusively in the poem itself, for the writer the end of the poem comes not exclusively when the last word is written (which will probably not be the actual last word in the bottom right of the page, anyway), but also when the poem is placed in the world somehow. The poem is made whole and “finished” when it finds its place. We as poets are done with it at that point, and while it might be the end of our explicit relationship with its emergence (and thus its “end,” for us) we never really can determine where it will find a place in the world.

This final discussion of endings, then, would seem to hinge on two factors: one, where the writer places the last words of the poem, and two, the way that the poem finds its place in the world. Of the two, we obviously have much more control on the former than on the latter. We craft the thing in words, searching for an end, and that end is determined not exclusively by the writer’s decision, but also on the writer’s intuition of how and where the poem will be received by some public. There is the situation of the writer writing, facing the page, so to speak, and contending with what unfolds in that very private dialog, but there is also the very real fact that the poem will in some way be placed in the world (should it be something more than a diary entry), and the writer must contend with this, as well. Just as a poem begins in the context of the life of the poet and in the first admission of words on a page, the poem ends in the context of the life of readers after the last words are ascribed to the page. On the one hand, a poem has a fate with the poet and on the other it also a fate out in the world when the poet cuts it loose.

On the first hand, the poet’s genius in this regard is in privately knowing when enough is enough. Key here (if our theory and discussion of the myths surrounding fate are worth considering further) is that when the last words are admitted to the page, this act insinuates that the last of the fates (Skuld, in the Norse tradition) has cut the umbilical of the poem. From the poem’s beginning when Wyrd inspires the threads of the poem into being, through the writing process when Verðandi helps determine how best to mete out the poem, to the end when Skuld invites us to cut the thread, we see our fateful relationship with the poem unfold.

But this act is, ultimately, circular. As we consider the second of the two factors determining the poem’s end, we find that as it ends in our hands, it begins publicly in the world. In a circular mystery, as the poet cuts the cord, so too does the first fate (Wyrd) again begin to spin the poem’s thread into being in the larger, more public fabric of the world. The end of the poet’s explicit relationship with the poem’s becoming is the poem’s actual beginning as a thing in the world. It will go on, from hand to hand and reader to reader, finding new meaning and becoming itself over and over again as it spirals out from its maker.

But let’s not let the myth get too far-flung. In the previous description, it sounds as if a poem once made will wander the fields of the world in perfect unmolested passion. But fate would have it otherwise. Just as the first factor is wrapped up in the biases, skills, passions and artful choices of the poet, the second of the two factors is wrapped up in the biases, skills, passion and choices of the public. Consider, unromantically if possible for a minute, how the way that we release the poem into the world affects what it will become. Think of the politics of how the poet must find some way to distance him or herself from the poem so that it can take hold in the world and think of how the powers vested in that experience drive different readings, readers, etc. This is not so different, in ways, from how parents (should) over time remove their own explicit influence on their children, and the ways of doing this are as varied as the poetic imagination will allow. The politics of how books get published and how they are promoted; the ways poets read and introduce their own and others’ work; the way the politics of academic creative writing promotes itself; the oft-found resistance of poets to literary theory and interpretation— these all point to ways that we work to put the poem into the world so that it may live in a particular way after we are done with it. These all lead to different fates in the public where they end up.

So the fates have their say, but let’s not believe it is angels that carry them through their daily trials and tribulations. They are tied into the fabric of power that we all live in, and it would be naïve to say otherwise. This doesn’t in any way deny their fate, but rather augments it and places it into a real, vibrant and powerful world. Poems are typically put out in the world as published artifacts, and with that act of publishing (and the whole business of publishers) comes another side of the power politics that makes the poem live in particular ways. Consider, for example, the politics of Buddhist monks who write their poems with sticks on the surface of streams. Or people who self publish versus find a publisher (and the ethics of legitimacy that comes with both of these choices). Think how pleased we are to find a poem written on a subway wall or scrawled quickly in the margins of a used book we buy. What different fates these poems have, and how fulfilling to spend a life considering the implications of this fact. As we write again and again, weaving the various threads of language and experience together, we unify the disparate strands of a largely untenable life and then deliver it to the world. It is not mere coincidence when this happens. We may think of this process as fate and gain something from having done so.

_____

[1] I say this place “should be earned” rather than “must be earned” because, like any other thing in the world, a poem can be forced, through whatever power would compel it, into being. Many poems, like so many other things, would never see the light of day without a well-known byline or the endlessly repetitive capabilities of the internet to propagate them. To acknowledge this is to make ourselves aware that to let a poem emerge well we must marry it to power wisely and skeptically. Does this power, we might ask, move the poem into the world in a way that allows it to keep emerging as itself? Of course most of us are simply glad that someone will put them out there for us…but I believe poets need to reconsider this process at times. The affirmation and validation of an editor publishing our work shouldn’t blind us into placing the poem somewhere it can’t really live. So often it’s a forgivable offense, as we work so hard to write the poem, we are grateful to have anyone publish it. This obviously isn’t so much a call to abolish publishing as it is, but to bring the question to the fore, especially with the rise of the web and all the new ways of getting poems into the hands of a public that will live with them, and ask us to reconsider how the inertia of the publishing industry and academia have perhaps set us on a course where our desire to publish in a “reputable” venue is sometimes not in the best interest of the work. This should be a primary ethical concern for poets.

[2] Note that here I don’t say “predestined,” as this would be a different kind of fate from what I am talking about. With predestination there is no free will, no choices made. The fate I is describe is destined, but not predestined. I’ll discuss this more later.

[3] And, beyond mere pragmatism, would lead us into a common philosophical error, an error that Continental Philosophy has spent much of its time trying to correct, namely what Edmund Husserl calls in The Crisis of the European Sciences the “mathematization of nature,” where we take the abstract language of mathematics as real, and the grounded, concrete language of the everyday as secondary to that. In this error, facts are primary and the ethical and felt experiences that obviously produced those facts are made subjects to the facts that they create. In this erroneous inversion, we understand meaning as “words about words,” an agony of language that is so obviously untenable and yet so widely believed that we must state otherwise in order to make sense of the theory at hand. This kind of inversion can and does happen, I believe, when we mistake meaning as something gotten on a page, as if words lived in a dictionary and not in the peoples’ lives who retain them. It is caused, I believe, largely by the literate mind objectifying the word (as a thing on a page) so much that it comes to seem to exist on its own, out “there” somewhere, and the best we can do is try to correlate our experience to it, filling its vacant spaces with the visceral stuff of our lives. In this error, a word becomes a room in search of a tenant, rather than a tenant in search of a room.

[4] Writing is different from speaking face-to-face in this way, but there is obviously a lot in common between the ethics of “where will it end up?” that we ask when we write something and the “where are you?” that we are accustomed to when using cell phones, for example. The cell phone is a very literate device.

[5] And consider that while Plato’s teacher, Socrates, didn’t write anything himself, Plato largely wrote dialogs, or written discussion, and Plato’s student, Aristotle, wrote books more like we have come to expect them to be: dense, defined, and exceedingly logical in a way that only a writer can be. See Eric Havelock’s The Muse Learns to Write and Walter Ong’s Orality and Literacy and The Presence of the Word for how writing has influenced this ethical question.

[6] Particularly there is an interest in Martin Heidegger’s work on the pathe, or the Greek concept of the emotions, and how the emotions are not just things we feel, but are, as tied into our bodies, the grounds on which language always sits. If I am to take these claims from Heidegger and many of his commentators as valid, then I risk emphasizing one aspect of the rhetorical trinity discussed previously. I would correct this by saying that each of these aspects grounds us...reason through articulate communication, definition and fact and ethics through trust of the whole situation where we speak and write. Daniel Gross contends brilliantly with the questions of the relationship between the pathe and the “rhetorical situation” in his introduction to the collection Heidegger and Rhetoric (SUNY Press, 2005). For some recent scholarship on this question, I would turn the reader to Claudio Ciborra’s essay ""The Mind or the Heart? It Depends on the (Definition of) Situation". Journal of Information Technology. 2006: 129-139; Thomas Rickert’s "In the House of Doing: Rhetoric and the Kairos of Ambience". JAC 2004: 901-927, "Toward the Chora: Kristeva, Derrida, and Ulmer on Emplaced Invention". Philosophy and Rhetoric. 2007: 251-273, and "Invention in the Wild: On Locating Kairos in Space-Time." The Locations of Composition. New York

[7] This is a particular tyranny of a particular logic that I am trying to avoid. The syllogism goes like this: my inability to express the full compliment and implications of my actions at every scale means that I must be either everything or nothing. An Absolute Yes or and Absolute No. This tyranny comes from the modern, literate compulsion to want to articulate and say everything in the world in order to bring everything within the fold of Reason. This kind of thinking led, for example, the Buddha to call for a Middle Way that disallows either extreme. We are everything and nothing, he might say, but normally our desires keep us wrapped up in a world where neither extreme is true. If we are going to have a world at all to talk about, it is going to be something between these extremes. We live everyday between the extremes when we’re not thinking about it, anyway, but a particular kind of reasoning would have us, ipso facto, say that it is otherwise.

[8] I say “typically cannot” in order to leave room for those religious and meditative traditions that would claim to allows us, however fleetingly, do so.

[9] And I’ll trust that we all have our favorite prosody bible for help with this.

[10] Irish literature also has its own version of the fated hero where the taboos of the protagonist (often established at birth) are systematically broken, bringing about the doom of the hero. A classic case of this is the Togail Bruidne Dá Derga (The Destruction of Da Derga’s Hostel), where the protagonist, Conaire Mór, given a set of taboos at birth, systematically breaks them and dies on a battlefield accordingly.

[11] Although it is interesting to note that with oral poetry which has no written equivalent (therefore in cultures that have no writing), the words unfold as events rather than as things. Thus there is no “revision,” so to speak, of an oral performance. (And certainly, an oral poet wouldn’t call it “revision” anyway, as there is nothing to re-visualize.”) The fabric of the oral poet, eventful and happening, is very much like the unfolding of the lives of the listeners, and presumably magical in a unique way because of it.

[12] And see the sections previously on meaning and meter for ways this may play out.

[13] See Biographia Literaria chapter XIV.

[14] This is not to say that all poems must be in strict accentual-syllabic meter and that the reader, having gleaned that the meter is, say, trochaic hexameter will expect the same throughout. Free verse poems, too, have a metered contract, and while it may be irregular in how it scans, it is nonetheless expected when the reader reads.

[15] The chiasmus form being common in Greek and other literatures, where the beginning is brought back at the end, often in a reverse order, to show closure. The term comes from the Greek letter chi (X), which has a crossing point where the sides reverse. The chiasmus, then, is the crossroads where the beginning meets the end.

[16] To be sure, as it is genealogical in how it is remembered, it is also generous in what it brings to the life of those who read it, in what it continues to generate in the text of the reader’s life. A poem, we might say, has its own genius.

_____

Sean M. Conrey is an assistant professor of writing and rhetoric at Hobart and William Smith Colleges in Geneva , New York Midwest Quarterly, Notre Dame Review and Tampa Review. His chapbook, A Conversation with the Living, was published by Finishing Line Press in 2009.

_____

RECONFIGURATIONS: A Journal for Poetics & Poetry / Literature & Culture, http://reconfigurations.blogspot.com/, ISSN: 1938-3592, Volume 4 (2010): Emergence

No comments:

Post a Comment